Why Can’t All Variants Be Confirmed by Sanger Sequencing?

What to know about family testing after Exome or Genome sequencing

After receiving Exome or Genome sequencing results, clinicians and families naturally begin to consider family testing.

- Was this variant inherited from a parent?

- Is it de novo?

- Is it present in other family members?

For this reason, many customers request family testing through 3B-VARIANT, 3billion’s Sanger sequencing–based family study service, after reviewing Exome or Genome results.

However, when attempting to proceed with 3B-VARIANT, some encounter the following message:

“This variant may not be suitable for Sanger sequencing–based family testing.”

If the variant is clearly reported in the result, why can’t family testing be performed using 3B-VARIANT?

In this article, we explain—based on real testing workflows—which variants can be evaluated with Sanger sequencing and which cannot, so that users can better understand what to expect when requesting family studies.

SNVs are usually feasible—why are CNVs different?

▪ SNVs (Single-Nucleotide Variants)

SNVs and small indels have clearly defined genomic positions at the nucleotide level. Because of this precise definition, they can usually be confirmed relatively easily using Sanger sequencing, and family testing can often proceed without issue.

▪ CNVs: where limitations begin

Copy number variants (CNVs) are fundamentally different. In many cases, key information is unclear, such as:

- Which exons are involved

- The exact breakpoint locations where the genomic rearrangement occurs

In Exome-based CNV analysis, CNVs are typically inferred from changes in sequencing coverage. While this allows detection of copy number changes, it often does not provide base-pair–level breakpoint resolution.

👉 Without precise breakpoint information, it is not possible to design appropriate Sanger sequencing primers, making confirmatory family testing by Sanger sequencing difficult or impossible.

Are there cases where even Genome sequencing is not enough?

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) covers a broader genomic region than Exome sequencing and is often more informative for CNVs and structural variants. However, even with WGS, breakpoint determination is not guaranteed in all cases.

What are “NGS dead zones”?

Although WGS sequences the entire genome, not all regions are equally analyzable. Certain regions are known to be difficult to interpret and are sometimes referred to as “NGS dead zones.”

These regions pose challenges for short-read sequencing technologies due to:

- Repeat-rich regions

- Low-complexity regions (LCRs)

- GC-rich regions

- Regions with low mapping quality, where reads cannot be confidently assigned to a unique genomic location

Recurrent CNVs and breakpoint ambiguity

A key issue is that LCRs are also regions where CNVs frequently occur. In particular, recurrent CNVs—those observed repeatedly across multiple patients—often have breakpoints located within these problematic regions.

As a result, even with WGS, precise breakpoint identification may remain limited, making Sanger-based confirmation infeasible.

Variant types that cannot be confirmed by Sanger sequencing

Beyond CNV breakpoint issues, several other variant types are inherently difficult or impossible to confirm using Sanger sequencing.

1. Repeat expansions

Diseases such as Huntington disease and Fragile X syndrome involve expansion of short repeat sequences, sometimes into dozens or hundreds of repeats.

- Accurate repeat sizing is difficult with Sanger sequencing

- Short-read NGS is also limited in these regions

2. Uniparental disomy (UPD)

UPD occurs when both copies of a chromosome (or part of a chromosome) are inherited from a single parent.

- The DNA sequence itself may appear normal

- Sanger sequencing cannot detect parental origin

3. Chromosome aneuploidy

Conditions such as Down syndrome (Trisomy 21) or Turner syndrome (45,X) involve abnormal chromosome numbers.

- Sanger sequencing cannot assess chromosome copy number

4. Mobile element insertions

Insertions of mobile elements such as LINEs, SINEs, or Alu elements can involve hundreds to thousands of base pairs.

- Insert size and repetitive nature often make Sanger confirmation impractical

5. Sanger sequencing “dead zones”

Sanger sequencing itself has technical limitations in certain sequence contexts, where accuracy may be reduced:

- GC-rich or AT-rich regions

- Homopolymer runs (repeated identical bases)

- Sequences forming secondary structures such as hairpins

In these cases, Sanger testing may be attempted, but the reliability of the result can be low.

Alternative methods when Sanger sequencing is not suitable

When a variant cannot be confirmed by Sanger sequencing, alternative approaches may be considered depending on the variant type and clinical context.

1. MLPA (Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification)

Useful for detecting exon-level CNVs in specific genes. However, MLPA requires a predefined probe set, so availability depends on whether a suitable kit exists for the gene of interest.

2. qPCR (Quantitative PCR)

Allows quantitative confirmation of CNVs by targeting internal regions. It is relatively fast and cost-effective.

3. Array-CGH or SNP array

Genome-wide CNV detection methods that can be used to compare CNV presence across family members.

4. Targeted genome sequencing

High-coverage sequencing of a specific genomic region to precisely define breakpoints. This approach provides detailed structural information but requires more time and resources.

5. Other variant-specific approaches

- Repeat expansions: Repeat-primed PCR, Southern blot, or long-read sequencing

- UPD: SNP array or microsatellite marker analysis

- Chromosome aneuploidy: Karyotyping, FISH, or QF-PCR

- Mobile element insertions: Long-read sequencing or specialized analytic pipelines

Summary

Family testing is an essential step in completing a genomic diagnosis, but not all variants can be confirmed using Sanger sequencing. In particular, CNVs and structural variants may be unsuitable for Sanger-based family studies when breakpoint information is incomplete.

In such cases, selecting the appropriate alternative method—based on the variant type and clinical question—is critical.

The choice of confirmatory testing affects not only technical feasibility, but also the accuracy of variant interpretation and the quality of genetic counseling provided to families.

📋 Checking 3B-VARIANT Eligibility Using Report Examples

A quick check before submitting your request

By reviewing the variant notation in a genomic test report, you can often determine in advance whether a variant is eligible for 3B-VARIANT, 3billion’s Sanger sequencing–based family testing service.

This quick check can help avoid unnecessary requests and delays before proceeding with family studies.

✅ Variant notations eligible for Sanger-based family testing (3B-VARIANT)

(Examples of report-style variant notation follow)

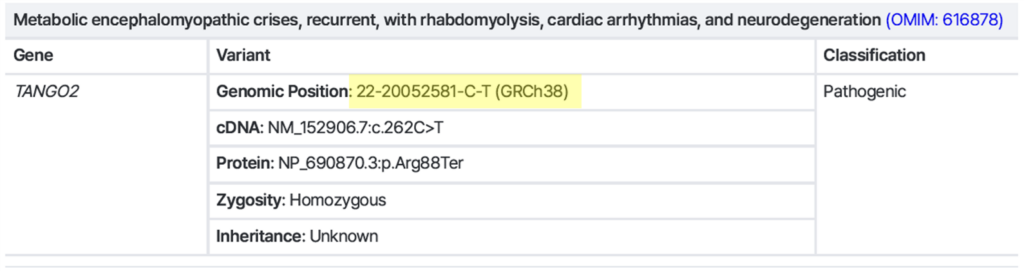

Example 1) Single Nucleotide Variant (SNV) / Small indel

→ Exact variant position is clearly defined → Sanger-compatible ✅

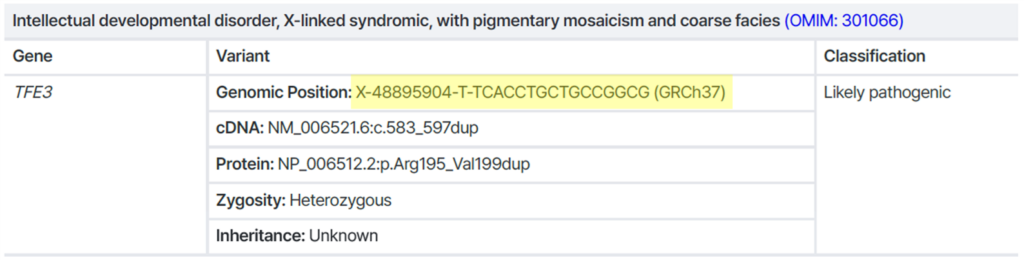

Example 2) CNV with a clearly defined breakpoint

→ Breakpoint is precisely identified → Sanger-compatible ✅

❌ Variant notations that are notsuitable for Sanger-based family testing (3B-VARIANT)

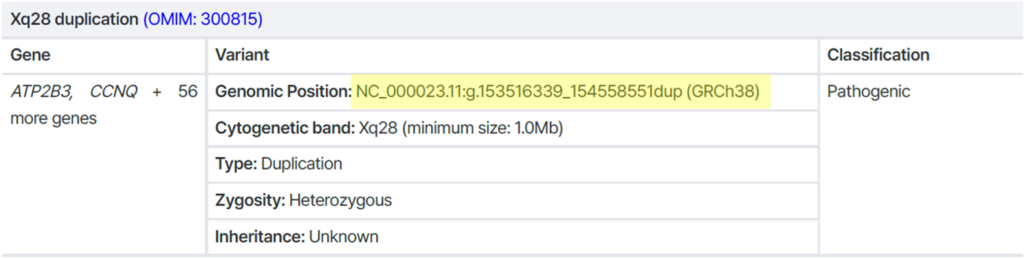

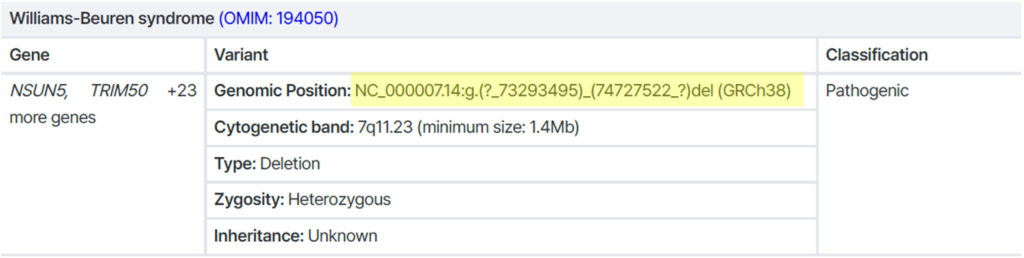

Example 1) CNV with an undefined breakpoint

→ Breakpoint is unclear (both ends annotated with “?”)

→ Not suitable for Sanger testing ❌

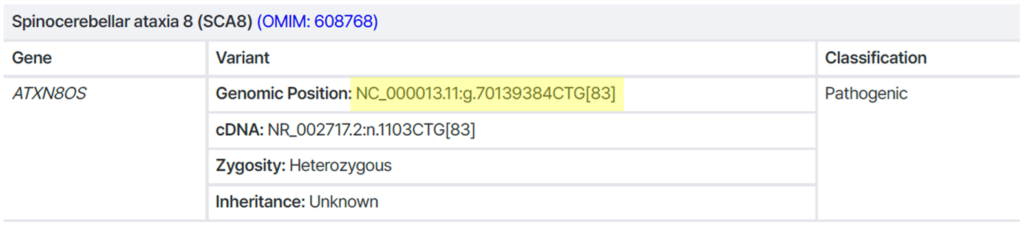

Example 2) Repeat expansion

→ Accurate repeat number cannot be determined by Sanger sequencing ❌

Recommended alternatives: Repeat-primed PCR, Southern blot, or long-read sequencing

Get exclusive rare disease updates

from 3billion.

3billion Inc.

3billion is dedicated to creating a world where patients with rare diseases are not neglected in diagnosis and treatment.