Wilson Disease: Diagnosis story

A boy diagnosed with Wilson disease

A few months ago, I received a phone call from a pediatric neurology specialist regarding one of his patients. I taught this specialist when he was an undergraduate and then when he was a master’s degree student at Sohag Medical School, and we have continued communicating. He knows I am interested in neurometabolic diseases, and he asked about Ahmed, a 7-year-old boy with a neurological disorder without a definitive diagnosis. Specifically, he was wondering whether it would be useful to have this patient undergo genetic testing to reach a final diagnosis and possible therapy.

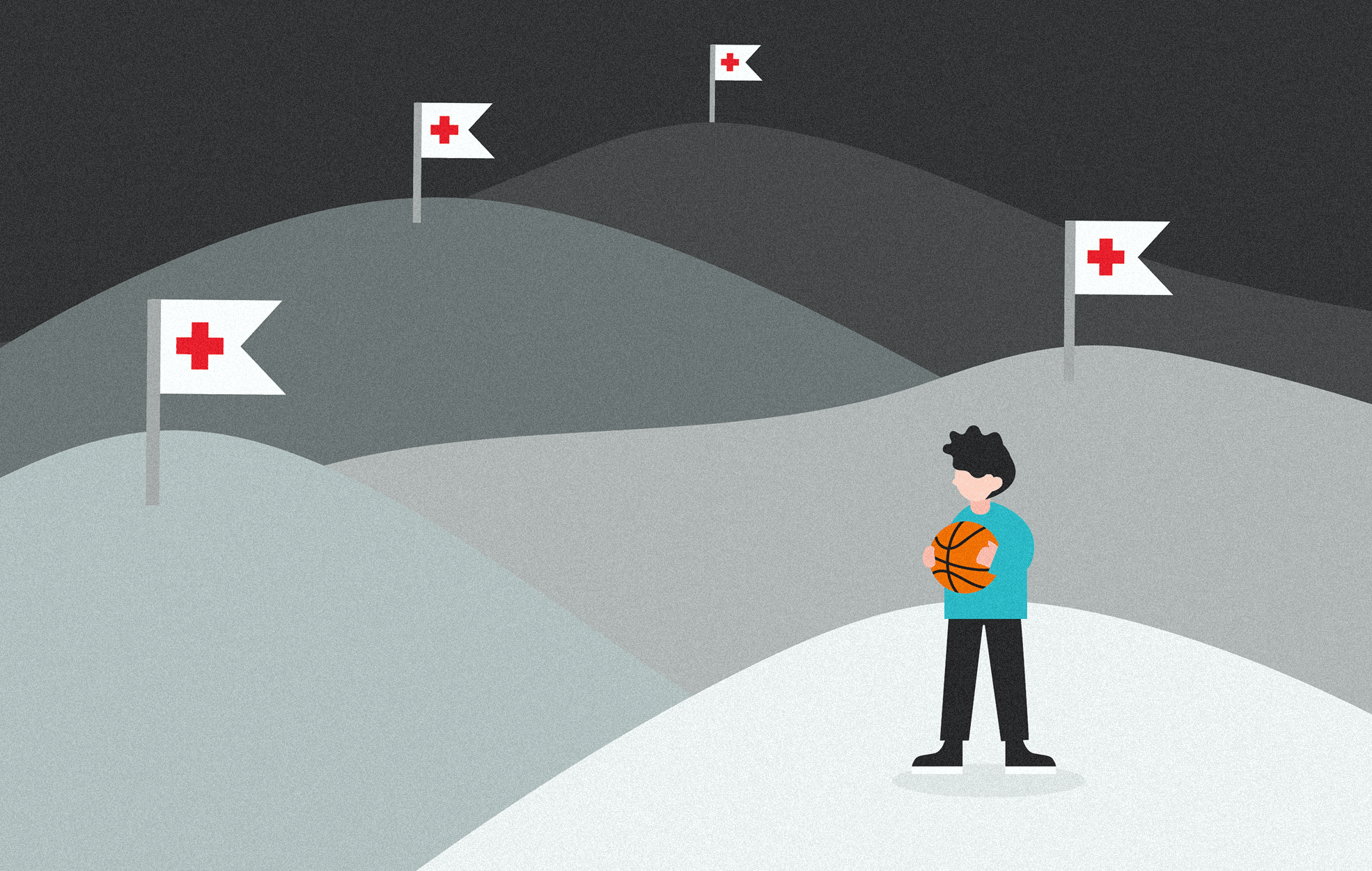

The next morning, Ahmed arrived at my hospital with his parents. He was walking with much difficulty, supported by his parents, and had irregular involuntary movements. The parents looked sad and depressed. They have been visiting many physicians, performing several investigations, and trying multiple therapies for their child for more than 4 years, but their child was experiencing progressive clinical deterioration.

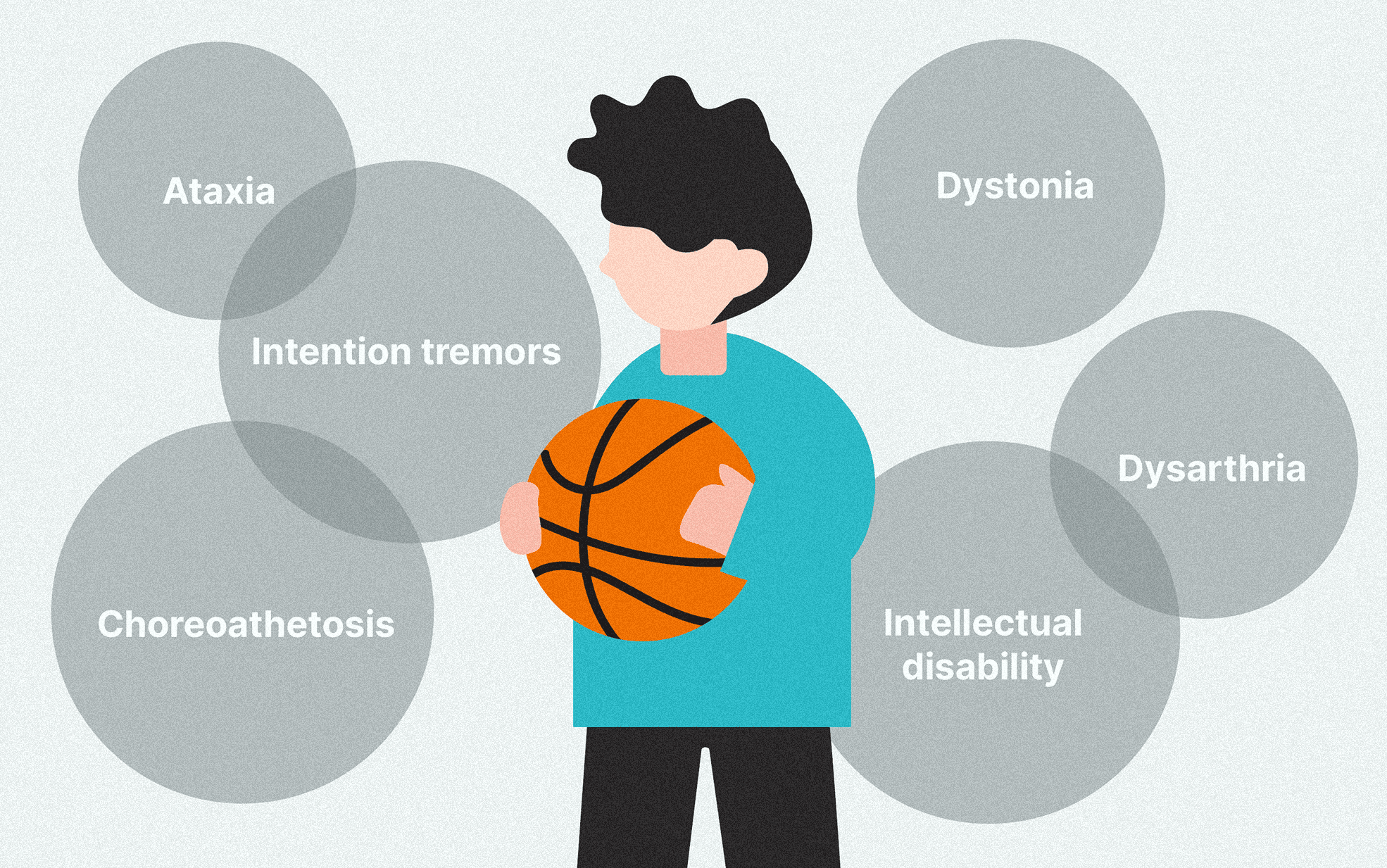

Ahmed was born at full-term by vaginal delivery without remarkable events during pregnancy, labor, and the immediate neonatal period. In the first three years, he had average speech and social communication but had a delay in gross motor development and achieved the walking milestone at the age of 2.5 years. At the age of 3 years, he started to have a slow progressive deterioration of motor function, with unsteadiness of gait, and difficulty walking without assistance. Moreover, Ahmed has suffered from a mixture of abnormal movements, including intention tremors as well as choreoathetoid movement. Speech and mentality were also affected with slurred speech and deterioration of school performance. Last, he has become depressed with intermittent episodes of nervousness and crying.

From the beginning of neurological deterioration at the age of 3 years, Ahmed’s parents have sought many physicians, who asked for several investigations, including brain imaging, chromosomal karyotyping, blood acylcarnitine profile, and urinary organic acids. However, the results of these investigations were not diagnostic. Some physicians provisionally diagnosed him with Ataxia Telangiectasia. During this period, Ahmed received a wide range of therapies, including cocktails of vitamins and tonics, physiotherapy, and behavioral therapy.

Upon physical examination, Ahmed had marked ataxia, intention tremors, choreoathetosis, dystonia, dysarthria, and intellectual disability. Moreover, there was mild liver enlargement, which has not been described by his prior treating physicians. After considering all this clinical information, we thought that Ahmed could have a neurometabolic disease, and that Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) would be a useful cost and time-effective method to conclude his odyssey. We had a comprehensive discussion with Ahmed’s parents to explain this genetic study. Thereafter, we obtained Ahmed’s blood samples, extracted DNA, and sent it to 3billion’s laboratory in South Korea as a part of a research collaboration.

Two months later, I received the results on my 3billion online portal. Based on clinical information and genetic findings, Ahmed had a genetic disorder called Wilson Disease. Afterward, we confirmed that Ahmed had low serum ceruloplasmin level, high urinary copper excretion, and Kayser-Fleischer ring in the cornea (by slit-lamp examination), which are consistent with Wilson Disease. Accordingly, we started a new treatment for Ahmed by dietary restriction of Copper, Copper-chelating agents, and zinc supplementation. Moreover, we are currently screening other family members.

Wilson disease (MIM #277900) results from mutations (gene abnormalities) in the ATP7B gene, which encodes essential regulators of copper excretion in bile. This leads to the accumulation of copper in the liver and then other tissues, including the brain and kidneys, which manifest as liver disease (e.g., hepatomegaly, acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis), neurological disorders (e.g., ataxia, tremors, dysarthria, choreoathetosis, dystonia, intellectual disability), Kayser-Fleischer in the cornea, as well as renal and hematological complications. Treatment with dietary copper restriction, copper chelating agents, zinc, and other modalities would help prevent the progression of liver cell failure/cirrhosis, neurological disease, and renal failure. Furthermore, early treatment would lead to improvement in hepatic and neurological function.

While it is still too early for noticeable clinical improvement in response to treatment, Ahmed’s parents are currently very pleased with not only reaching the final diagnosis but also starting promising treatment. They told me that “we hope we could have diagnosed and treated him earlier, but we are happy to finally make it”. I can’t forget the feeling that I had when I heard it, and can’t stop thinking about how WES could help diagnose, provide hope, and change lives for many potentially treatable cases like Ahmed’s.

Professor Dr. Elsayed Abdelkreem’s biography

|

Dr. Elsayed Abdelkreem is a lecturer of Pediatrics at Faculty of Medicine and Pediatric consultant at Sohag University Hospital, Sohag University (Egypt). His main clinical areas are pediatric intensive care as well as inherited metabolic and neurogenetic diseases. He has been working on several research projects on clinical and genetic characterization of children with organic acidemias, white matter diseases, neurocutaneous syndromes, and other rare diseases.

My goal as a doctor is to provide the best care for sick children, alleviate their suffering, and make their life better.

Get exclusive rare disease updates

from 3billion.

Sookjin Lee

Expert in integrating cutting-edge genomic healthcare technologies with market needs. With 15+ years of experience, driving impactful changes in global healthcare.