Why We Strive to Include Different Ethnic Groups in Rare Disease Research

Underrepresentation in medical research

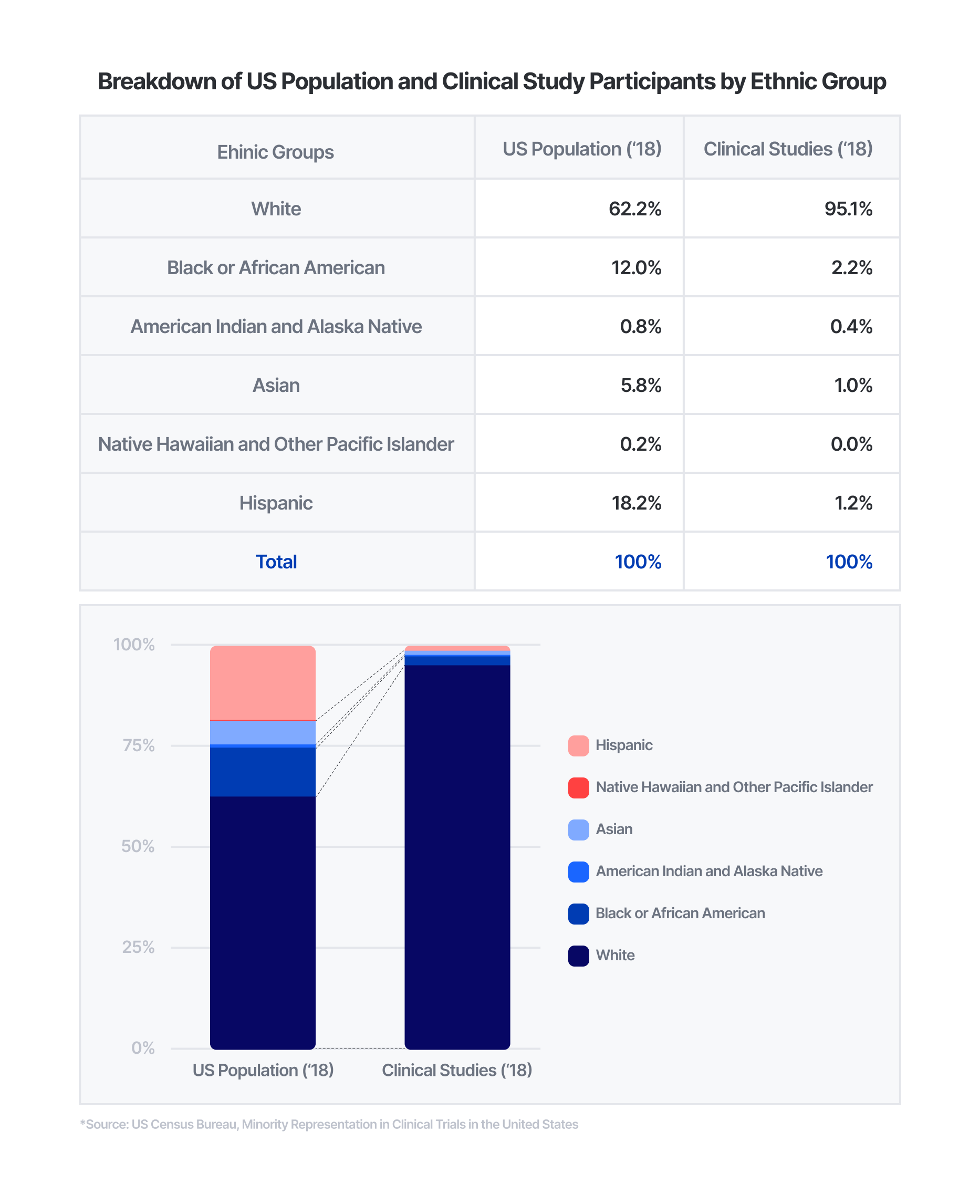

Historically, there has been underrepresentation of different groups in clinical studies. While recent efforts have been made to represent all members of society in medical research, women and different ethnic groups have been underrepresented for decades. Women make up 50.8% of the U.S. population, but only accounted for 41.2% of clinical trial participants from studies in 2016 to 2019. Similarly, ethnic minorities have also faced underrepresentation in clinical trials. Compared to non-White groups making up approximately 38% of the U.S. population in 2018, less than 5% of clinical study participants were from non-White groups in the same year.

To no surprise, the same applies to medical research on rare diseases. For instance, Egypt has one of the highest prevalence rates of Huntington’s disease, but has been largely excluded from studies. Huntington’s disease affects 2.7 out of 100,000 people globally, and 21 out of 100,000 in Egypt – which is nearly 8 times higher. However, there have been no studies that include patients in Egypt over the past decade. In the past 10 years, approximately four trials have been launched annually. Yet, none of the 130 studies involve patients from Egypt, which has over 100 million people and is larger than Germany in terms of population.

There are inherent difficulties in conducting clinical trials with adequate representation, especially for “orphan drugs”. While over 97% of non-orphan drug clinical studies accounted for differences in efficacy by sex, none of the orphan drug trials accounted for differences in sex, let alone ethnic groups. Research on orphan drugs is more prone to uneven distributions in sample populations due to smaller populations being affected by these rare diseases.

Why diversity matters in medical research

When certain groups are underrepresented, it threatens the universal right to health and increases the economic burden of public health care. Imbalances in clinical research participation hamper applications in drug efficacy, toxicity, therapeutic indices, and more. Moreover, it can also increase healthcare costs. It is estimated that the financial consequences of health disparities among ethnic groups amount to about 105 billion dollars annually, when adjusted for inflation. Health disparities are not only harmful to individuals, but also place a significant economic burden on society. Although it is difficult to overcome certain barriers, such as gathering an evenly representative sample for an orphan drug study, it is important to acknowledge these limitations and corroborate research accordingly.

Although fragmented, there has been progress in representing different groups in rare diseases research. While it is important to note that genetic disorders can affect any population group, Tay Sachs disease has shown higher prevalence among people of Ashkenazi descent historically. Carrier screening of Tay Sachs disease that began in the 1970s, has reduced the incidence of Tay Sachs disease among Ashkenazi populations worldwide by 90%.

In a broader sense, general clinical studies are involving more diverse groups of people. The NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 has fostered representation of traditionally understudied groups. More recently, the FDA finalized their guidance on enhancing diversity of clinical trials in November 2020. Additionally, in 2021, the American Medical Association partnered with the All of Us program, a historic research effort led by the NIH to study data from over one million people in the United States.

In the private sector, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) and its member companies published the industry’s first set of principles on clinical trial diversity in November 2020. Takeda, Novartis, Biomarin, and many other pharmaceutical companies are members of PhRMA.

Underrepresentation is an issue that needs to be addressed in all industries – especially in healthcare, as it is directly related to a person’s well-being and quality of life. This is especially important for 3billion, where we hope to make a difference for those who already feel like they are the minority.

Our efforts to improve diversity

Findings from 3billion’s research collaboration with the Undiagnosed Disease Program (UDP) were published in the American Journal of Medical Genetics in February 2022. Members from Stellenbosch University’s Division of Molecular Biology and Human Genetics, Tygerberg Hospital’s Medical Genetics department, and 3billion came together to evaluate the clinical utility of exome sequencing among South African patients suspected with rare genetic disorders.

South Africa has a diverse population with approximately 4 million rare disease patients. Next-generation sequencing is not widely accessible, and many patients belong to historically understudied sub-groups, leaving much room for further study. Our joint study was one of the first to evaluate exome sequencing in sub-Saharan Africa and the very first to enroll undiagnosed patients suspected with rare disease. The majority of patients were from traditionally underrepresented ethnic groups, with 45% being South Africans of mixed ancestry, 44% South Africans of African ancestry (mainly isiXhosa speaking), and 10% South Africans of European ancestry (mainly Afrikaans speaking).

It is pertinent that diverse population groups are studied due to differences in genetic variants. The incidence of a particular gene variant, also known as allele frequency, differs among populations. This genetic variation is what accounts for differences across individuals, such as eye color, height, susceptibility to certain diseases, and even responses to the same drug.

This is even more important for rare genetic disorders as certain population groups tend to have a higher incidence of a certain variant. If studies are limited to one population group, there can be an incomplete – and even incorrect – understanding of how the different variants are associated with disorders.

Patients from many parts of the world, including South Africa, currently lack access to exome sequencing. We hope that more programs like the UDP will help patients without a clear diagnosis find answers, and also help us gain a better understanding of understudied groups.

Get exclusive rare disease updates

from 3billion.